Post

Nietzsche: The Fast Track

The darkly dressed student made yet another existentially pessimistic remark and the professor unleashed one of the harsher insults I’ve heard:

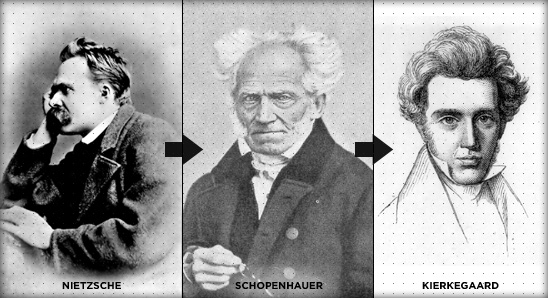

“Every student goes: Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard…” Ok, so maybe it’s not as bad as it sounded, but the accusation was that we (particularly as malleable young students) go through predictable stages of intellectual and spiritual development.

Nietzsche’s provocative philosophy challenged traditional Christian morality (“God is dead”), and his concept of the Übermensch is appealing as a template for the dominant, worthy human.

Schopenhauer (to whom the professor was associating the troubled student) proposed a more pessimistic philosophical system, finding the universe irrational and often cruel and painful. There were avenues to freedom, mainly through ascetically amplified levels of awareness, but they are long, difficult and rarely successful.

Finally, Kierkegaard’s philosophy was partly a theological account and described the uselessness of rationality in spirituality and the importance of faith. His concept of the “knight of faith” is of an individual who has absolute faith in God, who is nothing other than their faith.

Do we really all go through such similar and clearly demarcated “phases”? It’s worrisome to me because my own understanding (or ignorance) of life and existence differs significantly from the professor’s and most in their post-Kierkegaardean states, and with each phase shift, one’s ability to step back into their earlier state of understanding becomes more difficult. Despite the torture of not knowing much, I like the questions I’m thinking about and the grounding that what little I do know is indubitable. I fear that an inevitable phase shift (especially that last Kierkegaard one) will subdue my curiosity with leaps of faith, maybe as some kind of defense mechanism. Accompanying this suppression seems to be the dreaded “normal” life, the mindless nine-to-five existence that I – in my current state – vow to never succumb to (however unrealistic that may be).

Feedburner says there are over 1800 of you out there. Where are you, in terms of your age, daily activities/obligations, and intellectual state (it needn’t be of the three described accounts)? I don’t think I’m the Schopenhauer type, but I would say I’m a pretty even mix of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard (if that’s even possible with such polar characters).

Archive

-

260.

The Ethics of Practicing Procedures on the Nearly Dead

The report from the field was not promising by any stretch, extensive trauma, and perhaps most importantly unknown “downtime” (referencing the period where the patient received no basic care like...

-

260.

The Ethics of Teaching Hospitals

I can’t imagine what the patient was thinking. Seeing my trembling hands approaching the lacerations on his face with a sharp needle. I tried to reassure him that I knew what I was doing, but the...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Behavioral Science

Dr. Eran Zaidel is a professor of Behavioral Neuroscience and faculty member at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA. His work focuses on hemispheric specialization and interhemispheric interaction...

-

260.

Progress Report

Two years down, I’m still going. The next two years are my clinical rotations, the actual hands-on training. It’s a scary prospect, responsibilities and such; but it’s equally exciting, after...

-

260.

Why Medical School Should Be Free

There’s a lot of really great doctors out there, but unfortunately, there’s also some bad ones. That’s a problem we don’t need to have, and I think it’s caused by some problems with the...

-

260.

The Cerebellum: a model for learning in the brain

I know, it’s been a while. Busy is no excuse though, as it is becoming clear that writing for erraticwisdom was an important part of exercising certain parts of my brain that I have neglected...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Philosophy

Daniel Black, author of Erectlocution, was kind enough to chat with me one day and we had a great discussion – have a listen.

-

260.

The Stuff in Between

I’m actually almost normal when not agonizing over robot production details, and quite a bit has happened since I last wrote an update. First, I’ve finally graduated. I had a bit of a...

Comments

I’m not a philosophy major myself, so I can’t say which philosophers I identify with most, even though I am lightly versed on the above three. The problem I have is that I don’t think any of these philosophers really encompasses the state of humanity today, what is actually happening and how people perceive the world around them and themselves.

I find this happens a lot in old theory. Of course, the greats still have some very applicable ideas and possibly solid truths about us, but our world has changed so much since any of these philosophers was alive and doing work that there are likely many holes in the theories now.

Perhaps I am at a default to see things this way, considering I am a media student and have always found the function of media in society to be interesting, but I think the invention of mass media (radion, newspapers, television and especially the Internet) throws a wrench into a lot of old theories. We have so much outside information forming and/or influencing our thoughts about ourselves, the world and even God.

None of these theorists could entirely perceive the nature of the modern world, much less the post-modern world (which is ironic, since I know so many are interested in Nietzsche, at the very least, even today). I firmly believe we live in a media world, with all its positives and negatives, and that this alone has changed what can be considered true in much of philosophy, outside of perhaps the very basics of human nature.

It’s not that I don’t think these theorists, from what I know of them, don’t have some very valid points. I just don’t know if they can be applied as well, anymore, considering all the outside information influencing people these days. What do you think of that? Have your studies discussed this much?

I join you in your desire to avoid the nine-to-five hell.

Lelia Katherine Thomas

Apr 11, 07:49 AM #

That’s an interesting points of view of life right there. For what it’s worth, technically God can’t be dead. You may not believe in God but, God can’t be dead. An essential property to “God” is immortality (The beginning and the end). God do exist because it’s an idea. You may not believe in the idea but, it still exist. Or maybe I’m understanding it wrong.

As for Schopenhauer, his view is incredibly hard to justify or accept. Some people argue that life is rational and justified, the problem is we’re not life. We can’t comprehend everything, therefore we don’t include everything in our justification. Although we may think that something is cruel/painful, it may not really be cruel and painful if you account everything in existence. Consider a philanthropist billionaire who suddenly loses all his wife, children, and family. He would think of himself as the most unlucky person in the world. After all, he gives back to community and yet, he still loses the things he cared about. Our first thought would be, life is unfair. But when you consider the many people living in poverty across the world, who has to fight for their life, and may have lost their family as well, it’s not as unfair. Even though he lost his family, he still is a billionaire. Even though people living in poverty maybe in poverty, but they might still have their family. Of course this is an extreme case. But my point is, when one accounts everything, then maybe one can judge whether life is fair or not. But do I believe in this theory? I’m not sure, like I said, I don’t know everything therefore I can’t judge. I’m just throwing it out there.

Lastly for Kierkegaard, I don’t think a knight of faith is good for anyone, even God. If one chooses to be nothing other than his faith, than he has become completely dependent on God. Not only is he ignorant, but even when he did something wrong, he will blame God because he thinks God controls all his life. For example, imagine a man with a wife who is dying of cancer. Foolishly he denies treatment because he believe God is the doctor of all doctor and will heal his wife if God is willing. He won’t stop God from taking his course. Isn’t that stupid? I know this is a textbook case and there are still more variable such as “maybe God gave him money to save his wife”, but it proves my point.

Again I want to reiterate that I might just be playing devil’s advocate and it may not be necessary my point of view. I think part of being a good philosopher is to play the opposite side to make sure whether you really believe in what you believe. So I’m just throwing it out there. You decide what you think. Argue with me, and tell me I’m wrong and why.

P.S I’m a high school freshman, not a certified philosopher nor a certified designer (dang, I’m not very much am I…) I might have misunderstood the question. If yes, I’m sorry. After all, we’re all still learning.

Jonathan Solichin

Apr 11, 02:31 PM #

I can’t say that I am well versed with the three philosopher’s works but familiar enough to claim that I am definitely more on Kierkegaard’s end.

I fully acknowledge the need of faith in whichever belief systems we choose to accept. Our every day existence as we feel that we are part of is essentially based on the set of faiths we subscribe to (e.g., My intuition tells me that I am alive here and right now and engaged in typing this comment. Even though I can’t prove this on paper, I have faith in this idea)

I’ve written my thought process on this on my site which you might be interested in reading: Acknowledgment of systems and making choices

Sarven Capadisli

Apr 12, 07:15 AM #

That’s a great point. While the general concerns of these philosophers would likely still apply today, the way that we can access each other and information today is very different.

The problem seems to be that there isn’t much of that type of theory going on right now. Philosophy today seems to have fragmented into much smaller and more specific fields, and there isn’t much interest (aside from historical) in these grandiose universal frameworks.

That’s true, although Nietzsche may have been referring to popular beliefs about god (being dead). I’m not really sure.

This is actually something Kierkegaard discussed in his renditions of the biblical story of Abraham (who he thought was one of very few true knights of faith). Abraham was told by god to kill his son Isaac, and Kierkegaard interprets the most praiseworthy act of Abraham would be to actually go through with the killing and have faith that god knows what he’s doing. It’s an interesting point of view.

Ah yes, the cogito, how I’ve relied on you in my times of confusion. And, interesting write-up, thanks for sharing the link.

Thame

Apr 14, 05:09 PM #

I’ve had nothing but the merest brushing past caricatures of these thinkers, so I’m going to take your characterization as my only given. If our thinking is a product of our brain only, and not some disembodied, ethereal “mind,” and noting that human behavior, in aggregate, includes discernible and repeatable patterns, it’s only logical to conclude that many people will follow a similar path of philosophical enlightenment, building, testing, and refining their model of observation. There may be a class of such paths, such that there are different paths to follow; but I expect this class, generalized, is finite.

I remember, in high school, having the “What if the blue I see is your red?” conversations with friends, at about the same time I proclaimed I would write my own dictionary of the universe. I progressed pretty lazily (I like to think “patiently”) from there, taking small steps. A lot of my time I spent interested in humanity only insofar as I needed to, to negotiate the necessities of life, e.g. working, banking, buying groceries, etc.

Then I married a woman with three children, and added a fourth, and suddenly I couldn’t be so aloof without risking their livelihood. Moreover, I didn’t want to be aloof, except to gather my wits; I still haven’t developed some social skills I think some folks take for granted, and I’m overwhelmed by people from time to time.

The next seven years or so were basically fruitful, industrious, joyful years. I realized, though, that my wife and I were beginning to want different things more and more strongly. I hadn’t developed a strong sense of my own philosophy, at least not one which allowed me to distinguish what were rightful obligations to expect of me, and what were not. I let some things slide, I tried to become someone I wasn’t out of an interest to open up or unbottle a better person. Meeting someone else who seemed to value me for who I was at the time, rather than for my potential, put an end to that. I moved out, moved in with my future wife and two little guys, and three years later, we married.

I still haven’t come to grips with who I am, and how I’m defined by the actions of leaving my older children to live with their mother while I live elsewhere. I’ve grown, due in no small part to my lovely wife; but I have yet more growth ahead.

In the interim between divorce and marriage, I also had another child: a little girl named Ella. We found out, around the 18th week of the pregnancy, that she had Hypoplastic Left-Heart Syndrome, meaning that the left side of her heart wasn’t developing correctly. The typical course of treatment involves a series of three open-heart surgeries, to be completed by around the 5th or 6th year, but starting only a few days after birth. We had to weigh her potential quality of life with the notion of abortion. We chose life, though without admonishment for others who might’ve made the other choice.

The months leading to delivery were stressful, but we made it, and on July 5th, 2005, Ella came aboard. She cried quite loud, which I loved, taking it as a testament of her strength, that maybe she would be able to make it through everything we’d signed her up for. My wife and I were permitted to hold her for a few minutes, then she was rushed off for treatment. She left one hospital for another an hour or so later, in an enclosed incubator. We wouldn’t see her for a day or two, not until my wife was discharged.

A couple days after birth, the doctors took Ella to her first surgery. She soldiered through it, though it took an obvious toll on her small frame. Only after this were we told, in a passing comment of all things, that these three operations were only palliative, i.e. they did not repair anything, they just delayed the inevitably necessary heart transplant until sometime between 10 and 25 years of age. We were destroyed.

On October 7th, 2005, Ella died. We’re not sure what the cause was; we decided she’d been poked and prodded and defibrillated and examined far too much already, so we declined an autopsy.

At this point, philosophically, I’m having a tough time seeing any firm footing for believing anything beyond a shadow of doubt. I can’t see ever making it out from under that shadow, God and anarchy and altruism and all other compelling worldviews notwithstanding. At each of the points above, any confidence I had in whatever model I was using diminished, and I feel crippled and immobile sometimes now, unable to sort through what I should do.

The closest I get is to consider that behavior (we can constrain this to human behavior, but it is probably generalizable) has two components: a core, motivating earnestness; and the education about how to apply that earnestness. I don’t mean education in the strictly academic sense, rather I include classical conditioning, natural cerebral pattern matching, etc. I expect few people operate with a compromised earnestness, but rather the way they’ve learned to apply it (i.e. their morals) might be deficient (by some measure or another). Those extreme cases of “bad” people knowingly doing “bad” things seem to disentangle into people following an earnest belief that what is collectively called “bad” is not, in a tenably objective sense, anything of the sort. Thus, the murderers might not fret over murder because they don’t subscribe to moral code which directs such fretting, and might consider the culture’s assessment of “bad” to actually boil down to “inconvenient” or “morally challenging” or something. I suppose this is “moral relativism”, more or less.

I used to criticize the religious, above and beyond false piety, but I now basically equate their deities as labels, a classification system, a model, for their observations. Not all models have the same explanatory nor predictive power, but not all models serve the same specific ends, I guess. Further, I know of folks for whom subscription to a religious model is a function of conformity, who earnestly attend church and pray and beseech their god(s) because that’s the result of their education, their conditioning. They may not, in fact, believe there exist one or more actual deities, and that such belief is not a requirement of their “faith.”

As to the Kierkegaardean perspective, it could be that, after living long enough to approximate how trivial and small we are, folks gain respect for the grandeur they can’t fully comprehend. It could be, further, that these Kierkegaardeans call this grandeur “God” or some other religiously-natured label since (a) we don’t have a language capacity to fully describe It All anyway, and (b) because they think there’s no sense quibbling over one or another limited terminology for infinity. I don’t know.

Just as I’d be surprised that there weren’t a finite class of paths of philosophical enlightenment, I’d be surprised if I haven’t developed a worldview many others currently share, and have shared historically. I’m probably experiencing another generalizable phase. This tells me that, as a species, we don’t seem to be making too much progress. The real question is: what constitutes this “progress,” and to what end would we develop?

As far as I can tell, “survival” answers both.

Daniel Black

Apr 15, 09:32 AM #

Was Nietzsche a philosopher? Poet maybe…

machinehuman

Apr 15, 04:47 PM #

Daniel, thanks for your comment. I’ve read it over a few times and I’m sure it’s one I’ll be returning to when I need a bit of help. Your experiences and your responses are enlightening, heartbreaking, inspiring and profound. Seriously, thanks.

I can definitely agree with that. Especially given that the source of our philosophical questions and goals of our model-building are essentially identical.

This type of personal application is something I’ve had alot of trouble with recently. My abilities and work ethic are not in question; what’s difficult is the core motivation. The value of introspection and “listening to my heart” for this aspect are obvious, but I find myself notably inept at both.

I can see that too. Every time I look up there’s a desire to just surrender to faith in the immensity and beauty of existence.

Good point. Justification and, frankly reasoning, is almost completely absent. Has philosophy changed (he was certainly considered a philosopher in his time)?

Thame

Apr 20, 10:02 AM #

Nietzsche > Schopenhauer > Kierkegaard

=

High School > College > “real life”

I think I followed this path pretty much as the professor described it. I once had an 84 year old professor tell me I was the most cynical student he had ever spoken with, so I can understand how the student felt.

I would say that I am still far more cynical than Kierkegaard, but having a 10 month old definitely changes your philosophical perspective.

Mark

Apr 24, 01:34 PM #

It takes sorting through thoughts and constructing them into digestible chunks to make a different sense of them sometimes. There are likely things I could’ve articulated differently, but it was a sequence of things I’d been meaning to start documenting. Your post was the perfect opening grounds.

Here’s where some of the difficulty arises from semiotics/semantics, and a finite lexicon from which to draw terms to (re)use in new contexts. I might revisit my chosen terminology, but I don’t mean “motivating earnestness” to carry any positive (nor negative) terminology. The electricity a computer uses is neither good nor bad, but is its source of motive power (“motive power” being a description I’ve shamelessly stolen from Ayn Rand), and the instruction sets making use of this power range from “Hello World” programs, to intricate grid-enabled computations of protein folding, to Robert Morris’ worm. The power is neutral in any possible moral regard, and my thus far crude contention is that the person is an amalgamation of such a neutral (arguably biochemical and emergent) source of power and whatever instruction set(s) she cobbles together over a lifetime.

This would be intrinsically tied to, but not necessarily identical to, what we loosely call “motivation,” something that would echo “work ethic.”

Just as technology seems to pass a threshold of our discretion and becomes indistinguishable from magic, so too does the sheer monstrosity that is the universe around us exceed our faculties, becoming indistinguishable from divinity. I personally think we just put a label on all that we can’t fathom to make it easier to consider, and in some cases have overlooked that to take the label itself to be intrinsic to the universe. Of course, I can’t say for sure.

I’m hoping to start a more focused attack on these thoughts. I have to be careful to avoid taking my own handwaving too seriously, a la Deepak Chopra’s metaphors, e.g. “software of the soul,” etc. Without a real framework on which to hang my thoughts, that’ll be tough. We’ll just have to see how it goes.

Thanks, again, for providing a space here. It’s so easy to find places on- and offline where rhetoric is the end to which folks apply their means, but Erratic Wisdom has so far managed to avoid this pitfall. Excellent job, to Thame and the folks who stop by.

Daniel

Daniel Black

May 4, 03:32 PM #

Mark:

Hey cool, that supports the timeline I think the professor was suggesting. I don’t think I’ll have a Schopenhauer so I guess I started real life!

Daniel:

Thanks.

The “motive power” and electricity examples help, although now my worry becomes much broader: how do I select the “right” instruction sets (whether in a vague moral sense, or in terms of the most focused, successful application of my own motivating earnestness)? Is it a moral failing to power unworthy instructions?

Thame

May 6, 08:59 PM #

Exactly. Begs the question as to what constitutes the rightness or moral correctness of an instruction set. No matter where I start, I can’t seem to find any universal foundation on which to build such assessments conclusively. We’re almost begged to “follow our hearts,” but this is feeble; Genghis Khan followed his heart, and (forgive my invoking Godwin’s Law) did Hitler. Clearly, they’re not considered to have acted morally.

Seems, then, so far, that this rightness is a function, not of something universal, but of a local appropriateness. That’s another compromising term, but the idea is that the measure of rightness varies with the situation, with the context, with the culture. Bear in mind the demarcation problem; depending on your point of view, “culture” might only include one or two people, and isn’t necessarily only relevant to large groups of people.

So, by this reasoning, I might choose not to eat my vegetables and so forfeit my dessert. The dessert was offered as a ploy; my parent probably thinks eating my vegetables is the “right” thing for me to do. But unless there’s some objective standard that validates this, I’m just as right to agree to the terms offered and leave both the vegetables and the dessert on the table, untouched. Similarly, thieves may steal for a variety of reasons, but the rightness of these acts might only be assessable in light of their context. Thus, the underpinnings of our judicial system.

To be honest, if there’s nothing more than what amounts to moral relativism, if there are no inalienable human rights (I can’t find anything but hopefulness as any kind of evidence that there are), then we’re all a bit lost, wandering our cognitive paths trying to make good decisions. I’m sometimes paralyzed by the choice of what shirt to wear, because I’ve wrapped so much up into the decision itself. Choosing whether to bring a child into the world knowing she’s seriously ill, or choosing whether to stay in a faltering marriage to provide an in-home father for my children. . . . These were quite difficult. Some things seem to have become only moreso in recent years, thus my search for a calculus of decision.

Daniel Black

May 7, 06:27 AM #

The “local appropriateness” or moral reference ties back into the post and these philosopher’s accounts. For Nietzsche, some of the people you mentioned might be considered morally praiseworthy “supermen” in that their local appropriateness was entirely “local” (that is, their own will). Genghis Khan was probably the epitome of the Nietzschean Master. For Kierkegaard, the reference was God. The idealized knight of faith, Abraham, was willing to kill his own son (certainly, something we would normally find at least slightly questionable), but this was admirable, a sign of complete faith in God. There’s the cultural relativism that governs broader social guidelines, and perhaps more importantly, an inter- and intra-personal relativism of personal relationships, emotions and ego. The latter scope may come painfully close to “follow our hearts”, but I dare say our moral judgments more often stem from direct communication and experience than abstracted utilitarian assessments.

There is, however, something comforting in this relativism, it’s that each of us is the fulcrum of our own little scale. What I decide to be moral will change from day to day, but it’s a balance that I keep, and something that I will continue to struggle with. I should try to think less about other people’s scales and more about the balance that I can be

comfortable withproud of.Thame

May 9, 11:02 AM #

I wonder if we’ve been conditioned to want something more universal, that this sort of ultimate localization of moral standard is off the mark. Certainly, managing the logistics of any group of people numbering more than one becomes a bit harder if every individual’s code is equally “valid,” and as the vast majority of people interact with some kind of group, this underpins our living experience. I don’t know what to do with that: obviously, my relative freedom to follow what makes sense to me derives from a presumption that others need to respect my autonomy; but, again, where do we get off deciding murderers don’t have the same freedom?

That’s a bit sensationalist of me, and is a tired line of questioning; but I don’t see much other than practicality in the general presumption of “human rights” which provide for some positive and negative rights. They make group dynamics a bit simpler, but that’s not necessarily proof of any validity with which they’re connoted.

Daniel Black

May 11, 07:48 AM #

I learn here and there from them all, but I certainly can relate the most to Kierkegaard; especially in his approach to evangelism.

M.joshua

Jun 5, 07:39 AM #

Nietzsche

Studied classical philosophy. He was, undoubtedly, a philologist, philosopher, poet, musician, and author. His writing often lacks the stilted dry analytic process that characterizes so much of analytical philosophy (which seems to be the most common form taught, at least in the US).

Two good tests of philosophical development. Do you really understand what Nietzsche said when he said that “God is Dead”? Do you understand the significance or implications of the claim that “Relativism is not true for me”?

Michael

Jun 8, 07:55 AM #

It’s funny, I’ve been studying Nietzsche for years, since i was 17 (22 now) and I agree with this development. However, I doubt that I will follow that. Not because I don’t want to or that I feel its wrong, but because I found a new thought about the world. I’m sure others have said the same but I simply feel that what we call god is something that needs to include everything. everything was made in gods image as they say and i believe or feel at least, that if this is the case then everything is god, and everything we do to try and understand the world and ourselves is the study of god. I believe that atheist did us a service in the death of god because in his remains harvested the birth of our true ignorance of the world and in our ignorance a new god. the all unspoken and unknown. But what do i know, i didn’t even go to college

bob dole

Jun 30, 12:11 PM #

While the proposed continuum of Nietzsche —> Schopenhauer —> Kierkegaard might be true for some people, it is definitely not universally true, and I think it presents a flawed view of the philosophers involved. To place them in this order is to suggest that the level of complexity and maturity of thought is higher at Kierkegaard than it is at Schopenhauer than it is a Nietzsche. I don’t think that’s fair, because all three broke new ground in their own right, and altered the philosophical world. There is a complex interplay between the theories of all three men and later thinkers who studied them. At the very least, it is Schopenhauer who should be subordinated — while a key thinker, his pessimism does not capture the fluidity of life because it is essentially a one-sided analysis. Nietzsche arguably walks the most difficult line, indulging at times in both the rampant negativity of Schopenhauer and the irrational optimism of Kierkegaard.

For me, a better continuum is Schopenhauer —> Nietzsche —> Camus, or perhaps even nihilist reading of Nietzsche —> existentialist/absurdist/pomo reading of Nietzsche.

The reason Schopenfauer is first on my list is because in order to create new forms, you must destroy old ones. It is the burning philosophical ransacking done by Schopenhauer that provides the open space for thinkers like Nietzsche to grow.

Nietzsche is second because he takes up Schopenhauer’s project of destruction, but begins to develop avenues for creativity and creation within that project of destruction. The will takes on a new life in Nietzsche, and there are passages where he gloriously celebrates life itself. That joy, that attempt at embracing the world, is a more mature evolution of Schopenhauer. I’m probably still at my Nietzsche phase — creating, destroying, discovering, chaos, rebuilding.

The final, more adult phase, is Camus (or I suppose Kierkegaard if religion is your bag, but I always thought religion was Kierkegaard’s blind spot rather than his shining accomplishment). Camus does not purge the creation/destruction instinct, but he goes further in directing it towards some self-created meaning. He, too, realizes the futility of the project and the ultimate meaninglessness of the world, but he also seeks enlightenment in the form of meaning-making. Humanity manifests itself, fully and completely, light upper brown and dark underbelly alike, in Camus’s work. In this sense, he is the perfection of Schopenhauer ‘sand Nietzsche’s projects.

Horizon

Jul 1, 10:30 AM #

If I was going to propose a developmental path i’d personally suggest Kant – Schopenhauer – Nietzsche as a more sensible evolution.

All three have similarities which is hardly a shock since each takes on the one before in their own way.

Truth be told for me it’s more case of when you get tired of sifting through the mire of Kants writing style and inflated text, and the grow weary of the arrogance of Schopenhauer, you eventually wind up with the almost clear Nietzsche. Interestingly enough Nietzsche is the only one of the three who retains any semblance of relevance in the modern age, and cetainly the only one a modern student can genuinely relate to. Cynical? Yes. Nihilistic? Possibly. Valid? Certainly.

I still view Nietzsche as the first of the true post modern philosophers despite the fact he will never be accepted as such. I find his work ironic and cynical but deeply resonant in his ability to hit the nail on the head.

Karl Dammer

Jul 4, 07:05 PM #

it could be naive that God is dead; or maybe it is not all utility or action but transcendence; or simply, corruption begets perennial shortage. why begin to ponder in these three persons instead of just One?

Manuel G. Visaya

Aug 5, 07:47 PM #

I discovered this page via StumbleUpon and enjoyed reading some of the discussion going on amongst the various posters relating the Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard so I thought I’d throw in my own two cents…

To begin, I should note my Derrida-ian disposition and apologize for any metaphyiscal violence I may do to the comments made by the professor but I don’t think the suggested “progress” of thought holds. That being said…I want to be up front and say that it was Nietzsche who was the first philosophy who really resonated with me as an individual. My roommate lent me a copy of “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” before I went on vacation and I read the book cover to cover and understood very little of it. However I loved the writing, I loved the few themes which I was able to grasp and yearned to know in greater detail what he was talking about. I expanded my reading to other books by Nietzsche and eventually took a college course on Nietzsche. While I love Nietzsche for various reasons, pessimism is not one of them. When I read Nietzsche I am struck by an almost profound and deep sense of joy and sadness, playfulness and excitement, and a revived and new outlook on life. To think Schopenhauer’s pessimism is a “natural” consequence of this type of thinking strikes me as suspect (especially since the Schopenhauer-influenced Nietzsche later rejects many aspects of Schopenhauer’s thought as overly pessimistic and nihilistic).

It wasn’t until a few years later that I was formally introduced to Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard in graduate school and while I did find some of Schopenhauer’s observations slightly amusing, they weren’t for me. I thought Kierkegaard an interesting fellow but what I got out of him, more than anything, was the limitation of rationality on faith. While the limitations of rationality are already present in Nietzsche’s thought, Kierkegaard’s attempt to reconcile his faith with reason is one that is not easily reconciled. Thus the “leap of faith” which must be taken if one is to be a Christian. From what I remember of Kierkegaard this “leap of faith” wasn’t entirely dogmatic in that it made reason subservient to faith, but more so in recognizing that reason had limitations.

“The problem I have is that I don’t think any of these philosophers really encompasses the state of humanity today, what is actually happening and how people perceive the world around them and themselves.”

A valid point, however I’m almost positive Nietzsche (if not Kierkegaard) would agree with you on that point. Which, consequently, is why Nietzsche and Kierkegaard are relevant today. Although I’m not sure what Schopenhauer would say about the world today (I imagine it sucks), Nietzsche and Kierkegaard were both concerned about the lived life of individuals and their situation. Both of these authors are often considered proto-existentialists (if not existentialists in their own right). Philosophy should be lived, experienced, etc. I can’t speak too much for Kierkegaard at this point, but when I read Nietzsche, I do get a profound sense of contemporariness if not timelessness which I feel can be readily applied in any age: the destruction of old forms which no longer speak to our experience and the creation of new life enhancing forms. I would challenge anyone to read “On the Genealogy of Morals” and come away feeling the work is irrelevant today.

“Perhaps I am at a default to see things this way, considering I am a media student and have always found the function of media in society to be interesting, but I think the invention of mass media (radio, newspapers, television and especially the Internet) throws a wrench into a lot of old theories.“

Both Nietzsche and Kierkegaard had some pretty damning things to say about the press. Kierkegaard was often the object of ridicule in the public press and Nietzsche believed the press exacerbated the creation of the herd mentality based around the lowest common denominator. I am often reminded of their comments, especially during election years…

“That’s an interesting points of view of life right there. For what it’s worth, technically God can’t be dead. You may not believe in God but, God can’t be dead. An essential property to “God” is immortality (The beginning and the end). God do[es] exist because it’s an idea. You may not believe in the idea but, it still exist.”

The phrase “God is dead” is often attributed to Nietzsche, however I think it was Hegel who first coined the phrase (and even he may have been quoting someone else for all I know). “God is dead” is not to denote the existence of an actual God, but rather, as the above comment suggests, the idea of a God. Nietzsche is of the opinion that the current notion of the Christian God is a decadent God. This comes through in his analysis in the “Anti-Christ” but also pops up in “On the Genealogy of Morals” where he argues that Christianity has waged a war on science, the senses, the body, art, etc and is itself nihilistic in that it sacrifices the enhancement of life in this world by placing the value of life in the next, thereby degrading the value of the lived life in this world. But the death of God is not something which Nietzsche takes lightly. Nietzsche is afraid that with the decline of Christianity there will be nothing left to fill the void. The possibility of nihilism is therefore a state of affairs Nietzsche wishes to combat with the appeal to new forms of creation in order to fill the void left by the death of God.

As for my progression from Nietzsche. I’m currently engaged in the examination of Buddhist philosophy and am working on a masters thesis on Merleau-Ponty.

Kevin Beasley

Aug 6, 07:10 PM #

The entire premise of this “argument” (could positivists even call it an argument?) is truly absurd. If we were to bugger with the likewise absurd notion of linearity, a reverse chronology as the one you suggested, should be assumed. But as Nietzsche argues in The Will to Power, his writing represents the twilight of Christianity, thus, cough, Kierkegaard, and the advent of amoral nihilism. A better and more appropriate transition (although I still believe that premise is unrealistic) would be from Nietzsche to Matisse or Nietzsche to Beethoven (backwards!)

Allen Wilcox

Nov 21, 09:58 AM #

“God is Dead” Nietzsche’s most famous quote and probably one of the least understood.

In addition to its challenge towards Christianity, Nietzsche said that well into the Industrial Revolution, an age where science and technology was providing answers to lifes questions, not god.

There was also the shift of societies cultural center points from churches to museums and library’s.

Tyler Jay

Jan 25, 11:30 AM #

Add a Comment

Phrase modifiers:

_emphasis_

*strong*

__italic__

**bold**

??citation??

-

deleted text-@code@Block modifiers:

bq. Blockquote

p. Paragraph

Links:

"linktext":http://example.com