Latest Post

The Cerebellum: a model for learning in the brain

I know, it’s been a while. Busy is no excuse though, as it is becoming clear that writing for erraticwisdom was an important part of exercising certain parts of my brain that I have neglected lately. I have a few Conscious Conversation interviews in queue as well that I’ll be posting soon. So let’s begin.

The cerebellum is a beautiful organ, nestled just under its bigger brother. It’s a critical part of controlling movement and serves as an excellent, if simplified, example of learning and memory – with the structure itself helping us understand how it works. The cerebellum provides rapid corrective feedback along the route from upper motor neurons (UMN) in the cortex to lower motor neurons directly innervating muscle. Firing an UMN triggers muscle contraction, but directed movement involves the sustained and coordinated firing of groups of agonist and antagonist muscles that is regulated by structures like the basal ganglia, relay nuclei and our little friend. The cerebellum helps to smooth and fine-tune movement based on its inputs: somatosensory, proprioceptive, visual, auditory and vestibular (hence its defects present with balance problems and with fine motor difficulty).

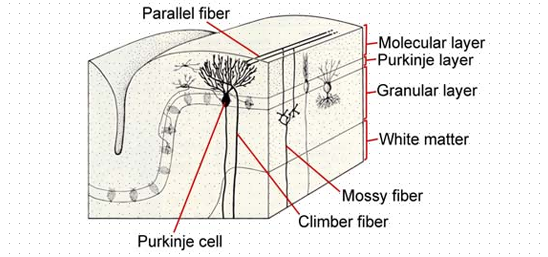

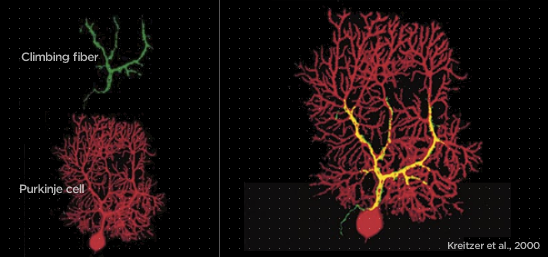

The cellular anatomy of the cerebellum explains a lot about how motor learning works. There are three major types of cells interacting in the cerebellum: Purkinje cells, climbing fibers (from the inferior olive), and granule cells and their parallel fibers. Purkinje cells provide the major output from the cerebellum, firing tonically to suppress movement. They have a large but flat dendritic tree and are stacked along each other in the outer layer of the cortex. They receive nearly 80,000 inputs each from parallel fibers shooting past their dendrites and a single strong input near the body of the Purkinje cell from a climbing fiber. The parallel fibers transmit contextual sensory information from the rest of the brain, while the climbing fibers ascend from the inferior olive and deliver a powerful, complex spike when an error is noticed during a novel task.

Let’s use an example to put this system into motion. Imagine we are trying to learn to respond to a new stimulus. Just like Pavlov’s dogs, we want to associate the response to an unconditioned stimulus, with a conditioned stimulus. When we deliver a puff of air to the subject’s eye, they blink. What we would like to do is associate a tone just before the puff with the blink. We now have a stimulus (the tone) that is sent to the Purkinje cells by parallel fibers, and an error (failure to blink) that is delivered by climbing fibers. This simultaneous activation sets the stage for memory and learning.

When the subject fails to blink in time, the climbing fiber slaps the Purkinje cell for its error, and the Purkinje cell responds by punishing those parallel fiber synapses that were active when the complex spike was received. Activity from the complex spike travels up the dendritic tree to meet with coincidentally active parallel fiber synapses and promotes the removal of neurotransmitter receptors at only these synapses, an enduring process known as long-term depression. Now, the next time the tone is heard, the Purkinje fiber responsible for tonically inhibiting eye blinks is no longer stimulated by the tone-activated parallel fiber and its tonic inhibition relaxes, promoting the desirable blink.

It’s an incredibly elegant system, suitable for such an elegant little brain.

Archive

-

260.

The Ethics of Practicing Procedures on the Nearly Dead

The report from the field was not promising by any stretch, extensive trauma, and perhaps most importantly unknown “downtime” (referencing the period where the patient received no basic care like...

-

260.

The Ethics of Teaching Hospitals

I can’t imagine what the patient was thinking. Seeing my trembling hands approaching the lacerations on his face with a sharp needle. I tried to reassure him that I knew what I was doing, but the...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Behavioral Science

Dr. Eran Zaidel is a professor of Behavioral Neuroscience and faculty member at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA. His work focuses on hemispheric specialization and interhemispheric interaction...

-

260.

Progress Report

Two years down, I’m still going. The next two years are my clinical rotations, the actual hands-on training. It’s a scary prospect, responsibilities and such; but it’s equally exciting, after...

-

260.

Why Medical School Should Be Free

There’s a lot of really great doctors out there, but unfortunately, there’s also some bad ones. That’s a problem we don’t need to have, and I think it’s caused by some problems with the...

-

260.

The Cerebellum: a model for learning in the brain

I know, it’s been a while. Busy is no excuse though, as it is becoming clear that writing for erraticwisdom was an important part of exercising certain parts of my brain that I have neglected...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Philosophy

Daniel Black, author of Erectlocution, was kind enough to chat with me one day and we had a great discussion – have a listen.

-

260.

The Stuff in Between

I’m actually almost normal when not agonizing over robot production details, and quite a bit has happened since I last wrote an update. First, I’ve finally graduated. I had a bit of a...