Latest Post

On Subjectivity

Science places a heavy emphasis on the objectivity of the physical world. As a result, consciousness, and specifically its subjective aspect, is often understandably ignored. What interests us is not the experience of heat, but real heat, the underlying physical reality of molecular motion, collisions, etc. However, to say that the final scientific “picture” contains nothing subjective seems to ignore a large (and significant) part of our universe. It is important to note that when I say subjective, I mean the first person nature of conscious experience, not something based on opinion or personal feelings. Subjectivity is the most immediate and inexplicable aspect of consciousness.

Rather than just deny the existence of subjectivity (something I’d like to see anyone try without proving themselves wrong), we should try to understand what it is and its place in the universe.

First, to solidify the point I’m trying to make about subjectivity, I’d like to quickly lay out what is known as the Knowledge Argument. Here’s the scenario, presented by Frank Jackson in his (1982):

“Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like ‘red’, ‘blue’, and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal chords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence ‘The sky is blue’. (…) What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not? It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then is it inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete.”

If Mary learns something new, then we seem to show that subjectivity (qualia) does exist and that it is quite different from the objective knowledge she held while in the black and white room.

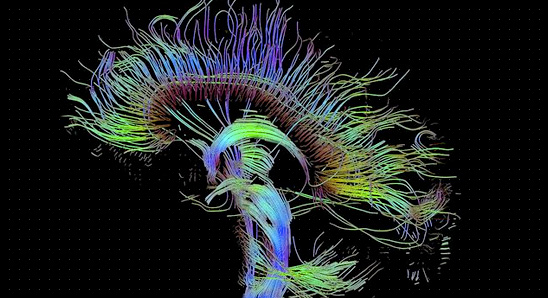

Now, if we know that all mental processes are caused by the brain, and that the brain operates according to physical laws, how can a collection of neurons produce subjectivity? How can mere pulses of electricity create consciousness, a feature unlike anything else in the (objective) universe? I really have no idea.

But, let’s try a few thought experiments to see what we can learn. If, as I’ve posted earlier, consciousness is a complex collection of sensory input and motor/behavioral output, then does removing any or all of these channels cause a decrease or loss in the subjective aspect of consciousness? If I suddenly lose all of my senses (sight, hearing, position, etc.) and even become completely paralyzed (save for whatever is needed to keep me alive), I don’t believe I’d lose the subjectivity of consciousness. I’d perhaps get very bored and lonely, deprived of the sensory fix I so desperately need, but I would still have my thoughts and memories.

So, what is consciousness? What produces the subjective experiences that are so significant to me (that, in fact, define me)? It could be a separate region of the brain, some kind of coordinating or binding center. However, that seems to just push the problem into a mind within the mind. Everything I’ve learned about the brain shows that it’s a highly interdependent system, and saying that any one region has a single function is almost universally false.

Another option is that subjectivity is a “learned” process like language. Let’s return to the thought experiment. When I lost my sensory faculties, I maintained my subjectivity, but what if I were born in that condition (senseless and paralyzed)? Now the situation seems a bit different, but why? The difference is that I have no memories of stimuli and responses to fall back on.

A baby is born without subjectivity, merely reflexes and innate behavioral responses. However, as it receives new stimuli and experiences new things, it begins to learn from and form memories of these events. If the brain can compare incoming stimuli to memories of similar stimuli (which seems to be a big part of how the mind works), then there is a link between a past and present pre-subjective perceiver (p-p-potentially). Imagine we have a newborn who is crying. The cause is hunger contractions which trigger pain receptors and eventually his crying response. I should note that the infant does not experience pain, they are merely physiological responses at this point. Moments later, he sees friendly figures and reflexively initiates a feeding response which causes a cascade of responses ultimately producing satiety and he stops crying. A few hours later he begins to cry again from the same cause. This time around, the baby has a memory of the last feeding experience. The diff, so to speak, of the incoming stimuli to his memory leaves behind his now unpleasant hunger relative to the pleasant satiety he experienced earlier and he (perhaps consciously) initiates the behaviors that resulted in his feeding earlier.

The brain is still a physical machine, a computer. Features like subjectivity seem far-fetched for the computer in front of you, but maybe not for the type of computer the brain is. It’s a huge and incredibly active organ, constantly creating and pruning connections among its 100 billion neurons (supported by 10 to 50 times as many glial cells). Your brain doesn’t crunch numbers, but raw sensory experience and maybe that makes subjectivity possible.

Jackson, F., 1982, “Epiphenomenal Qualia”, Philosophical Quarterly 32: 127-136.

Archive

-

260.

The Ethics of Practicing Procedures on the Nearly Dead

The report from the field was not promising by any stretch, extensive trauma, and perhaps most importantly unknown “downtime” (referencing the period where the patient received no basic care like...

-

260.

The Ethics of Teaching Hospitals

I can’t imagine what the patient was thinking. Seeing my trembling hands approaching the lacerations on his face with a sharp needle. I tried to reassure him that I knew what I was doing, but the...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Behavioral Science

Dr. Eran Zaidel is a professor of Behavioral Neuroscience and faculty member at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA. His work focuses on hemispheric specialization and interhemispheric interaction...

-

260.

Progress Report

Two years down, I’m still going. The next two years are my clinical rotations, the actual hands-on training. It’s a scary prospect, responsibilities and such; but it’s equally exciting, after...

-

260.

Why Medical School Should Be Free

There’s a lot of really great doctors out there, but unfortunately, there’s also some bad ones. That’s a problem we don’t need to have, and I think it’s caused by some problems with the...

-

260.

The Cerebellum: a model for learning in the brain

I know, it’s been a while. Busy is no excuse though, as it is becoming clear that writing for erraticwisdom was an important part of exercising certain parts of my brain that I have neglected...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Philosophy

Daniel Black, author of Erectlocution, was kind enough to chat with me one day and we had a great discussion – have a listen.

-

260.

The Stuff in Between

I’m actually almost normal when not agonizing over robot production details, and quite a bit has happened since I last wrote an update. First, I’ve finally graduated. I had a bit of a...