Latest Post

The Ethics of Teaching Hospitals

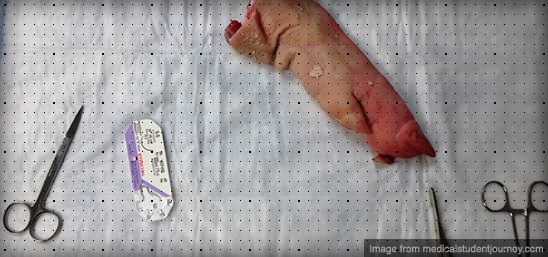

I can’t imagine what the patient was thinking. Seeing my trembling hands approaching the lacerations on his face with a sharp needle. I tried to reassure him that I knew what I was doing, but the pair of residents who stood behind me discredited that notion. The procedure took twice as long as a more experienced practitioner, but the end result was – in my perhaps biased opinion – comparable.

Patients at teaching hospitals, perhaps unknowingly, take a large role in the education and development of every stage of trainee in every area of practice. They will likely be interviewed and examined multiple times; their plans of care may change as their case makes its way up the chain of command; and they may undergo supervised procedures performed by less experienced trainees. However, I believe that patients receive superior treatment at teaching institutions as a direct result of the supervised care of trainees who are more curious, active and generally have fewer responsibilities and are able to spend more time with their patients.

Let’s explore the ethics of patient care at teaching institutions, examining how it may affect each of the major principles of medical ethics.

- Autonomy: Individuals have the right to make decisions about their health and what happens to their bodies.

I think there is some infringement on autonomy in teaching hospitals, as patients should expect to be fully informed in order to make reasonable decisions. While patients receive information about the hospital and consent for treatment during registration, it is unlikely that this information is either read or explained appropriately.

I have been guilty of this as well. For example, I intentionally withheld from a patient the fact that I had never performed a particular procedure outside of relatively low-fidelity simulations and had just watched a video explaining how to do it.

It does not respect the patient’s autonomy to hide these facts, as the patient has a right to know and potentially refuse treatment. - Beneficence: The practitioner must act to improve the patient’s health.

The application of this principle is unaffected in teaching institutions. - Non-maleficence: First, do no harm.

It is possible that the participation of less-experienced trainees leads to more errors and the possibility of causing unintended harm. However, the requirement for hands-on experience for trainees is unavoidable. Patient safety should be ensured with continuous supervision and graded responsibility. - Justice: All patients should be treated equitably. All resources should be distributed equitably.

Different teaching institutions vary in their levels of insistence on trainee participation (should a patient refuse that students not participate in his or her care). A violation of this principle would occur if certain populations were more likely to be required to work with trainees. Another possible conflict is if teaching institutions are predominantly located in low-income areas where patients have fewer options.

In summary, I believe that trainee participation in teaching institutions is critical to the development of competent physicians and is therefore an essential component of medical care. The participation of trainees supports the overarching goal of helping people, and the risk of harm can be mitigated by adequate supervision. Finally the principles of autonomy and justice can be upheld if all patients are adequately informed of the ways that trainees may participate in their care and none are allowed to refuse such participation without reasonable concerns.

Have you ever been treated or hospitalized at a teaching institution? What was your experience like?

Archive

-

260.

The Ethics of Practicing Procedures on the Nearly Dead

The report from the field was not promising by any stretch, extensive trauma, and perhaps most importantly unknown “downtime” (referencing the period where the patient received no basic care like...

-

260.

The Ethics of Teaching Hospitals

I can’t imagine what the patient was thinking. Seeing my trembling hands approaching the lacerations on his face with a sharp needle. I tried to reassure him that I knew what I was doing, but the...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Behavioral Science

Dr. Eran Zaidel is a professor of Behavioral Neuroscience and faculty member at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA. His work focuses on hemispheric specialization and interhemispheric interaction...

-

260.

Progress Report

Two years down, I’m still going. The next two years are my clinical rotations, the actual hands-on training. It’s a scary prospect, responsibilities and such; but it’s equally exciting, after...

-

260.

Why Medical School Should Be Free

There’s a lot of really great doctors out there, but unfortunately, there’s also some bad ones. That’s a problem we don’t need to have, and I think it’s caused by some problems with the...

-

260.

The Cerebellum: a model for learning in the brain

I know, it’s been a while. Busy is no excuse though, as it is becoming clear that writing for erraticwisdom was an important part of exercising certain parts of my brain that I have neglected...

-

260.

Conscious Conversation: Philosophy

Daniel Black, author of Erectlocution, was kind enough to chat with me one day and we had a great discussion – have a listen.

-

260.

The Stuff in Between

I’m actually almost normal when not agonizing over robot production details, and quite a bit has happened since I last wrote an update. First, I’ve finally graduated. I had a bit of a...